This article is an introductory summary of the teachings of Zen Master Thích Thông Triệt on the topic, mainly based on the oral teaching of Bhikkhuni Zen Master Thích Nữ Triệt Như given for the Intermediate Meditation Course Level 1. For a comprehensive in-depth understanding, the reader is encouraged to attend the complete nine-seminar teaching program and read the writings of Master Thích Thông Triệt that are being progressively translated into English.

The Buddha’s Enlightenment

After attaining the “three realizations”, the Buddha remained at the root of the bodhi tree for another seven weeks to contemplate the truths that he had realized. He returned to dwelling in the tathā-mind, i.e. to the state of immobility samādhi, in which he examined worldly phenomena. From his potential for enlightenment sprang new discoveries. He saw four characteristics of all worldly phenomena as well as their true essence. In this second realization after the first set of three realizations, he recognized the law of dependent origination and reached full enlightenment or “the ultimate enlightenment” (P: anutttara sammā sambodhi, V: vô thượng chánh đẳng giác) and became the Buddha.

The Law of Dependent Origination

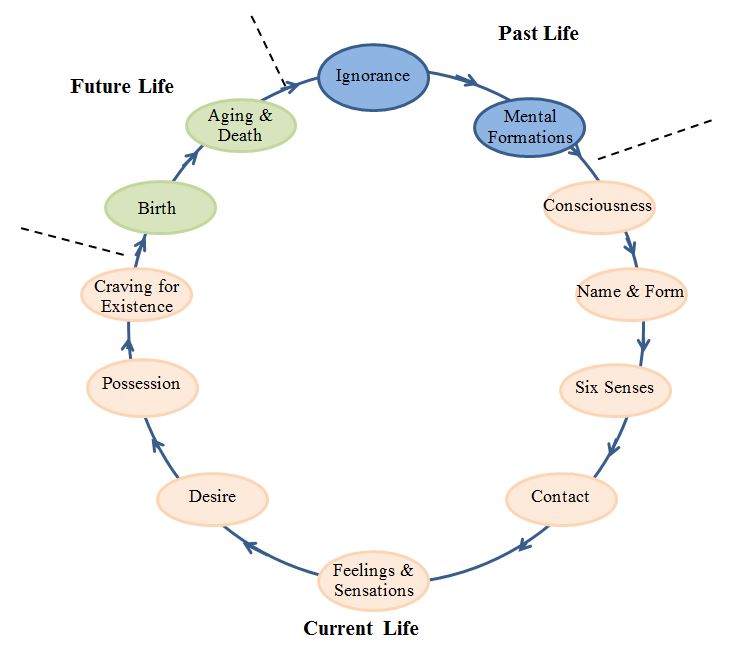

In the Khuddaka Nikāya “Minor discourses”, Book 3 Udāna “The inspired un-prompted discourses”, Chapter 1, the Buddha related that after attaining the three realizations, he continued his meditation for another week to contemplate the fruits of his enlightenment. At the end of this week, in the first watch of the night, he realized the law of dependent origination in forward order. He saw the law of cause and effect applicable to human beings. He saw the twelve causes or conditions and their effects in people’s lives, linked together in a closed-loop chain.

The Buddha saw that ignorance (V: vô minh) is the cause of mental formations (V: hành), as ignorance causes people to have states of mind like sadness or happiness. The cause “ignorance” results in the effect “mental formations”, or in other words “when ignorance is, mental formations are”. The sutta says: “Because this is present, that exists. Because this is born, that is born. From the cause ignorance, arise mental formations…”

The other pairs of cause-and-effect follow. Mental formations cause consciousness (V: thức), which is the urge to say or to act, generating speech or bodily karma. When a person dies, his/her consciousness escapes from the body and reenters another body when rebirth occurs. Therefore, consciousness causes rebirth, which starts with the creation of the body and mind of the new-born, which is his name and form (V: danh sắc). The word “name” is used to designate the four aggregates of the mind (feelings and sensations, perception, mental formations and consciousness) and “body” means the body aggregate. When the name and form of a new-born are created, the six senses (V: sáu xứ or sáu căn) are formed. When a person starts living life, the six senses come into contact with worldly phenomena, and hence contact (V: xúc) arises. When the mind comes into contact with the external and internal world, feelings and sensations (V: thọ) arise. With feelings and sensations come desires (V: ái). When we desire something, we want to take possession (V: thủ) of it. When we want to possess things, we want to keep living in this life and future lives to enjoy the possessions, this is craving for existence (V: hữu). Craving for existence is the energy that leads to rebirth. With birth comes the inescapable result of aging, sickness and death, summarized as aging and death. When we come to aging and death, all the suffering accumulates into a mass, called the suffering aggregate in the suttas. This suffering aggregate is the cause of ignorance, and from there the causal chain resumes.

In the second watch of the night, the Buddha saw the twelve causal conditions in reverse order. In the words of the sutta: “Because this is absent, that does not exist. Because this ceases, that ceases. If ignorance ceases, mental formations cease. If mental formations cease, consciousness ceases etc. Thus, the suffering aggregate ceases.” In other words, if ignorance ceases, suffering or the cycle of birth-aging-sickness-death also ceases.

In the third watch of the night, the Buddha saw the law of dependent origination in both forward and reverse orders: “Because this is present, that exists. Because this is born, that is born. Because this is absent, that does not exist. Because this ceases, that ceases. Therefore, ignorance causes mental formations. Mental formations cause consciousness, etc. This is how this suffering aggregate is formed. When ignorance ceases completely, all mental formations cease. When mental formations cease, consciousness ceases etc. This is how this suffering aggregate is terminated.”

The Buddha confirms that the law of dependent origination is an immutable law that applies to human beings and all worldly phenomena: “And now, monks, what is the law of dependent origination? … Whether the Tathāgata has appeared or not, the law stands, directs and regulates worldly phenomena…” (Samyutta Nikāya, Nidāna Vagga “Section of Causation” number 12, s ii 25).

After he realized the law of dependent origination, the Buddha attained full enlightenment or the ultimate enlightenment (P: anutttara sammā sambodhi, V: vô thượng chánh đẳng giác) and became the Buddha. The law of dependent origination became a central part of his teaching and appears in several suttas often under the name of the twelve links of dependent origination (V: mười hai duyên khởi or mười hai nhân duyên). The Buddha summarizes it in four verses:

“Because this is, that is

Because this arises, that arises

Because this is not, that is not

Because this ceases, that ceases.”

The Twelve Links of Dependent Origination

The Twelve Links of Dependent Origination depicts the twelve causal conditions that link together to form a chain of cause-and-effect (P: nidāna). They are the twelve causes or the twelve links in the chain that lead to human suffering and endless rebirths.

Buddhagosa (S: Buddhaghoṣa, V: Phật Âm), a pre-eminent Buddhist monk living in the 5th century AD, grouped the twelve links of dependent origination into past, current and future lives. Ignorance and mental formations are causes that shape the current life, and therefore are categorized as past life. The following eight causal conditions, from consciousness to craving for existence, constitute the present life. Craving for existence is the energy that causes future re-birth, that is the future life represented by birth and aging-and-death.

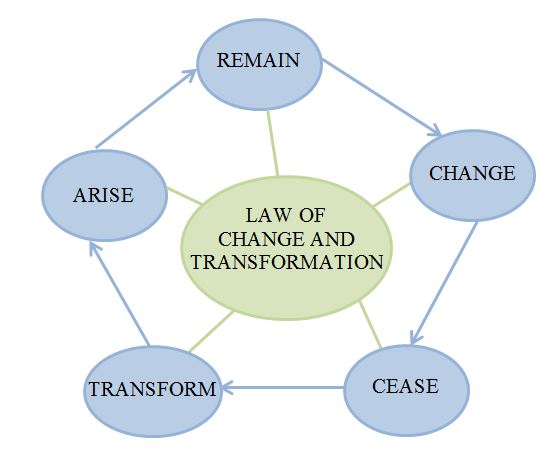

The twelve causal conditions form a closed loop, from ignorance to re-birth and aging-and-death. The twelve causal conditions occur ceaselessly, creating the endless cycle of birth, suffering, death and re-birth that forms the human condition. The energy behind the movement of causal conditions is the energy of change and transformation, which is one of the true characteristics of worldly phenomena that the Buddha recognized when he reached enlightenment. The law of change and transformation drives all worldly phenomena in every instant.

In order to end suffering and the endless cycle of deaths and rebirths, we can work on cutting through any of the twelve links. When one link is severed, the whole chain ceases to exist.

Buddhist cosmology

When the Buddha realized the law of dependent origination, he contemplated worldly phenomena and saw that all worldly phenomena, from the smallest, like a speck of dust, to the largest, like the sun, arise and exist due to many specific causal conditions. They are said to have specific conditionality (P: idappaccayatā, V: y duyên tánh).

The specific conditionality of worldly phenomena is encapsulated by the Buddha in the oft-repeated four verses:

“Because this is, that is

Because this arises, that arises

Because this is not, that is not

Because this ceases, that ceases.”

This represents the law of cause and effect applicable to the natural world. Underneath the law of cause and effect is the law of change and transformation which is the energy driving changes in shape, color, life and death of worldly phenomena. The Buddha saw this cycle arise-remain-cease as applicable to all worldly phenomena. When a phenomenon appears, it is in the arise stage (V: sinh). When it has existed for a while, it is in the remain stage(V: trụ). And when it finishes, it is in the cease stage (V: diệt). Later, patriarchs of the Developmental school of Buddhism added two more stages: change (V: hoại) and transform into another phenomenon (V: thành).

True nature of worldly phenomena

All worldly phenomena, including human beings, are subject to the law of change and transformation and undergo changes every tiniest moment of time. From this realization, the Buddha identified three characteristics of worldly phenomena: impermanence (V: vô thường), suffering (V: khổ) or conflict (V: xung đột), and no-self (V: vô ngã). Worldly phenomena change all the time, they are not permanent and ever-lasting, and, therefore, impermanence is one of their characteristics. People endure suffering and sorrow when they refuse to accept the law of impermanence. When applied to worldly phenomena in general, suffering becomes conflict, a force that drives changes in the phenomenal world. As worldly phenomena change continuously, they do not have anything permanent that can be called their true identity, and therefore, they do not possess an identity or a “self”. This is the no-self characteristic. The three laws of impermanence, suffering/conflict, and no-self are called the “three characteristics of worldly phenomena” (V: tam pháp ấn).

Human beings exist due to many causal conditions and, as a result, are not permanent, do not possess a true substance and do not have a fixed constitution. When the causal conditions cease to exist, so does the human being. The Buddha says that the true nature of human beings is emptiness (V: không tánh). Although the essence of all worldly phenomena is emptiness, we still see phenomena as existing before our eyes. The Buddha calls this existence illusion. Worldly phenomena are by nature illusion (V: huyễn tánh). Worldly phenomena change every second but our senses don’t perceive these changes. Therefore, what we see through our senses is an illusion like a mirage, a shadow or a dream.

When the Buddha realized the law of dependent origination, he saw the true nature of worldly phenomena. This true nature consists of suchness, indivisibleness, identicalness, specific conditionality, change and transformation, emptiness, equality and illusion.

Human beings and worldly phenomena all possess the suchness nature (P: tathatā, V: chân như tánh) and, therefore, they are all equal, giving them a nature of equality (V: bình đẳng tánh). Suchness is the true and complete reality. It cannot be divided (indivisibleness), it is the same in all worldly phenomena (identicalness), it does not change, it does not move, it is permanent and abiding, nothing can be added to it, nothing can be taken away from it. Suchness is the essence of all worldly phenomena. The Buddha calls it “the unborn”. It is also called an unconditioned phenomenon (V: vô vi pháp) as it is not formed by causal conditions, and, therefore, does not change or cease to exist.

Change and transformation is the ever changing characteristic of all worldly phenomena, changing from one form to another as a result of the ebb and flow of causal conditions. This is the endless cycle of births and deaths applicable to worldly phenomena. As all worldly phenomena are formed by multitude causal conditions, they are called conditioned phenomena (V: hữu vi pháp).

The emptiness characteristic recognizes that the true nature of worldly phenomena is emptiness.

And illusion refers to the illusion of appearance that our senses perceive, whereas the true nature of worldly phenomena is emptiness.

The Buddha later recounted his realization of the law of dependent origination in these terms: “And now, monks, I thought: ‘This truth that I have realized is profound, hard to see, hard to understand, pure, peaceful, sublime, beyond the realm of reasoning, subtle, and only the wise can experience it’” (Majjhima Nikāya, “The Middle Length Discourses”, Sutta 26, Ariyapariyesanā Sutta, “The Noble Search”, V: Kinh Thánh Cầu). In this sentence, a key idea is “beyond the realm of reasoning”, or in Pāli, atakkāvacara. This word is made up of “a” which means “not”, “takka” which means “reasoning” and “avacara” which means “realm”. Atakkāvacara indicates that the most profound teaching in the law of dependent origination such as suchness, emptiness, and illusion can only be experienced when we are in the state of wordless cognitive awareness.

![]()